Turning Bacteria into Genetic Circuits (Without Them Noticing)

Lately I have been summarizing every paper I read on a single piece of paper. Before I started doing that I would invest a lot of time reading a paper, and two months later it would completely disappear from my brain. The only thing I would remember is if I had found it interesting or not (not the most important information when trying to compile a bibliography). Limiting myself to a single piece of paper ensures that I only record what is important, and the fact that the notes are handwritten lets me triple underscore and use all the curvy arrows I need to make important ideas stand out. My two-month recall is now pretty decent.

I’m going to a seminar tomorrow presented by Tim Lu, one of the authors of a Nature Biotechnology paper titled Synthetic circuits integrating logic and memory in living cells. I decided to read the paper and write up a quick summary.

The paper describes a new technique to arrange the genome of a bacterium (E. coli) and turn it into the biological equivalent of an electronic circuit. This approach is much more scalable than previous techniques because using it to build complex circuits like an XOR gate doesn’t require joining universal gates together, which means that instead of assembling this madness:

you can assemble the XOR gate directly:

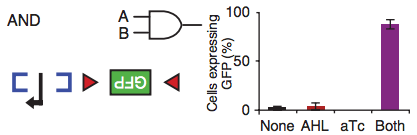

(By the way, a gate is just a way to convert two inputs into one output. Inputs and outputs can be either 1s or 0s. The type of gate (AND, OR, XOR, etc.) describes the rule that is used to make this conversion. For example, check out the table rule for the AND gate)

Stinginess is important because you can use as many components as you can fit in a circuit boards, but cells are much more puritan about the number of resources they allow.

The paper’s magic sauce is in the use of inducible recombinases—recombinases that become active when their inducer (a riboregulator) is added to the media. An activated recombinase can bind specific regions of DNA and flip their orientation, which in turn switches on or off the expression of their downstream gene.

For example, the blue brackets in the figure above represent the DNA binding site of a recombinase that, once activated by its inducer (input A), flips that region of DNA, making the promoter (black arrow) accessible to the RNA polymerase. But the RNA polymerase has nothing to transcribe unless the region between the red triangles is also flipped by a different recombinase. When this recombinase gets activated by its inducer (input B), the Green Fluorescent Protein gene can be transcribed and the cell starts making enough GFPs to turn the bacterium into a swimming Christmas tree. As the barplot shows, when both inputs are not present, the amount of GFP that is made is minimal (no biological circuit will ever be perfect).

(Just to clarify, GFP is an example, any gene can be integrated into this type of circuit. It’s just that a glowing bacterium is easier to detect than one that expresses the blond-hair gene)

That is just one possibility out of the 16 that appear in Figure 2 (check out the especially clever technique used to build the XOR and XNOR gates).

Because the recombinases modify the information that is stored in the bacterial chromosome, after a bacterium divides, the two daughter cells have the same genetic information, which means that next generations of bacteria will keep synthesizing GFP for centuries (days, in bacterium-years). DNA is what Nature uses as a hard drive, which means that coming up with clever ways to store information in it will bring us ever closer to genetically engineering the bionic pets we have all been dreaming about.

The paper is blissfully short, and worth a read if you think synthetic biology is cool.